Kali Yuga

A solo exhibition by Tasman Richardson

Arsenal Contemporary Art Montreal

September 17, 2019 - March 20, 2020

Arsenal Contemporary Art Toronto

March 9 - August 14, 2021

Press Release

Images by Romain Guilbault

Exhibition Essay

The Eroticism of Technology

“None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

- Goethe

“What our children have to fear is not the cars on the highways of tomorrow but our own pleasure in calculating the most elegant parameters of their deaths.”

- J.G. Ballard

“Most men and women will grow up to love their servitude and will never dream of revolution.”

- Aldous Huxley

In Hinduism the life of the world is divided into ages (yugas). At present, we find ourselves in the fourth and final age – the kali yuga – having drifted farthest from the divine and away from an age of truth, virtue, and righteousness. Ours is a period defined by a darkness, misery, and sorrow which, according to the Vedas, will culminate in the destruction of the world.

Kali is one of a host of goddesses worshiped by the Hindus. Often associated with death, some regard her as the most terrifying of the divine entities. She is often depicted as a blue or black skinned figure with red eyes and is drawn either without clothes or donning only a skirt made of human limbs. She is the goddess of time - a phenomenon she has the power to both create and destroy. For thousands of years Hindus have said that in the kali era, the human race will decay until it reaches its prophesied annihilation; then the cycle begins again.

Apocalyptic narratives have appeared overtime, resonating today with a particular urgency as water levels rise and earthquakes become more severe. Technology often plays a complex role in the story of the world’s end, surfacing both as its cause and remedy. While the path to total destruction varies across accounts, the final outcome is always the same.

J.G. Ballard’s Crash is but one of these dystopian narratives, which firmly plants its troubled characters within the kali yuga. The novel is set in an apocalyptic communications landscape, through which move “the specters of sinister technologies and the dreams that money can buy”. While recovering in the hospital following a car accident, the novel’s narrator (a television commercial producer also named Ballard) becomes infatuated, then sexually aroused, by both the driver of the car that he collided with, and even more strangely, the car itself. A masochistic former computer scientist named Vaughan shares these technophilic fantasies, experiencing arousal through vehicular violence, especially the driving deaths of celebrities. He fantasizes about committing suicide through a head-on collision with Elizabeth Taylor, and is the celebrated leader of a marginal group of techno-fetishists.

Technology plays a complex role in Ballard’s story, as an object of fixation, eroticism, and death. In a web essay published in 1996, David Goldberg presciently observes that, “attempts to expediate [sic] life through technology result in a gradual enslavement, as in the case of Vaughan. His obsession with crashes eventually destroys him”. The story of Crash ends with Ballard and his wife coordinating their own suicides, in a climax that combines the three themes permeating Tasman Richardson’s own oeuvre: sex, death, and technology. These are held to be the causes and symptoms of the kali yuga, which in Sanskrit translates to “the age of vice”.

The technological foment characterizing Crash’s mise-en-scène is unsettlingly familiar; its surface aesthetic dominates his characters’ realities, as can be equally observed in the hypnotic glow of the cellphone screens and computer monitors that illuminate our own lives. The postmodernists long warned that this condition of perpetual surfaceness would have deep consequences, extending beyond the realm of the aesthetic to manifesting at the heart of the human psyche and its passive habits. Ballard’s characters experience a flattening in their range of emotion, resulting in a deadening effect. Referring both to his characters and society at large, he notes in the introduction to the French translation of the novel, that, “voyeurism, self-disgust, the infantile basis of our dreams and longings -- these diseases of the psyche have now culminated in the most terrifying casualty of the century: the death of affect”.

Individuals over time have found a myriad of ways to cope with the dissociation that accompanies impending world doom. In Crash, Ballard’s characters are so devoid of feeling that they search for sexual stimulation through deliberate bodily injury. Compare Ballard’s vision with that of Aldous Huxley, who in Brave New World depicts his own brand of dystopian futurescape; one in which the population turns to a state-sanctioned drug called Soma, which allows its users to recede from the wretched realities of everyday life. Do we inhabit the doomed bodies depicted by Ballard and Huxley as those very same bodies floating aimlessly within the kali yuga?

According to Ballard, Crash is a fantasy that cautions against “that brutal, erotic and overlit realm that beckons more and more persuasively to us from the margin of the technological landscape”. Richardson’s works are sirens that lure us further into the centre of the world Ballard warns of. Pornography, narcissism, technology - these are pleasurable diversions that bind us together as they choreograph our false sense of freedom; vices which are the clear leitmotif of Richardson’s labyrinth.

In other words, the artist has realized the dystopian combination that Ballard first described, as a nightmare marriage of sex to technology. Like Crash, the exhibition is propelled by an apocalyptic fixation, and a perverse death drive. Where Ballard proclaimed Crash as the first pornographic novel based on technology, Kali Yuga accomplishes the same in exhibition form. Navigating its ominous walls makes you feel more alive, and yet closer to death. Telegraphing Ballard, in the darkness of the exhibition “the fantasies of our epoch and its technologies lie ruthlessly exposed to the light, evoking all the lyrical disenchantment of their failed promise”.

The effects of the exhibition are evident even before entering its hollow, with its pervasive technologies unable to be restrained by the gallery’s walls. A camcorder confronts us and captures our portrait, displaying it on an attendant monitor. The piece decays our image through a physicalized live feed, in a repeated pairing of camera and screen. Degrees of narcissism and self-loathing propel the photograph forward, in a cyclical mediation that renders our original image invisible and eroded, until, by the end, we are unrecognizable even to ourselves. This work is stealthily scattered throughout the space with an unsettling comprehensiveness. Going Gray (2019) references the completeness of social media’s effect on its users, alongside the insidious monitoring systems pervading our lives, both of which masquerade as instruments of safety, security, and conviviality.

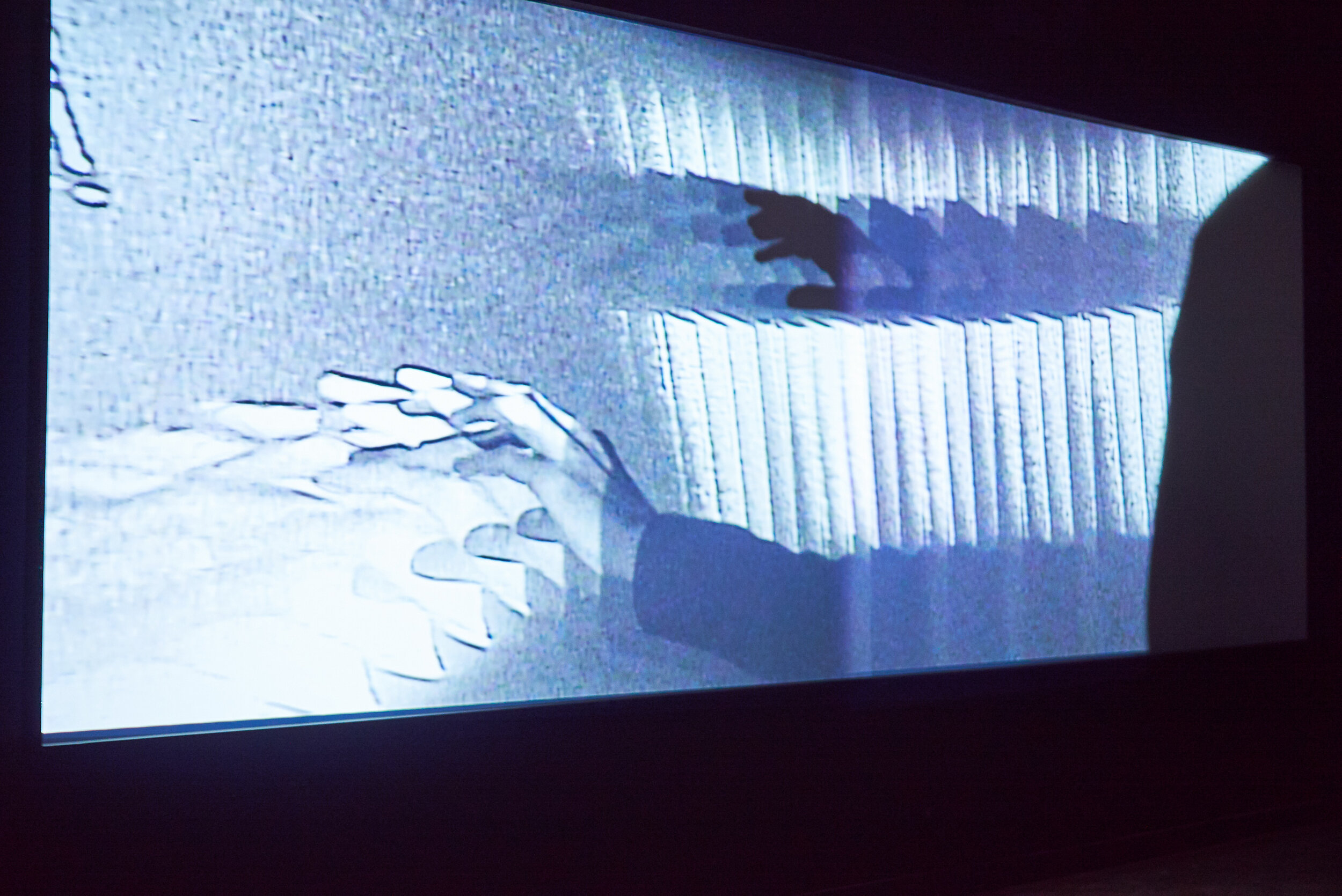

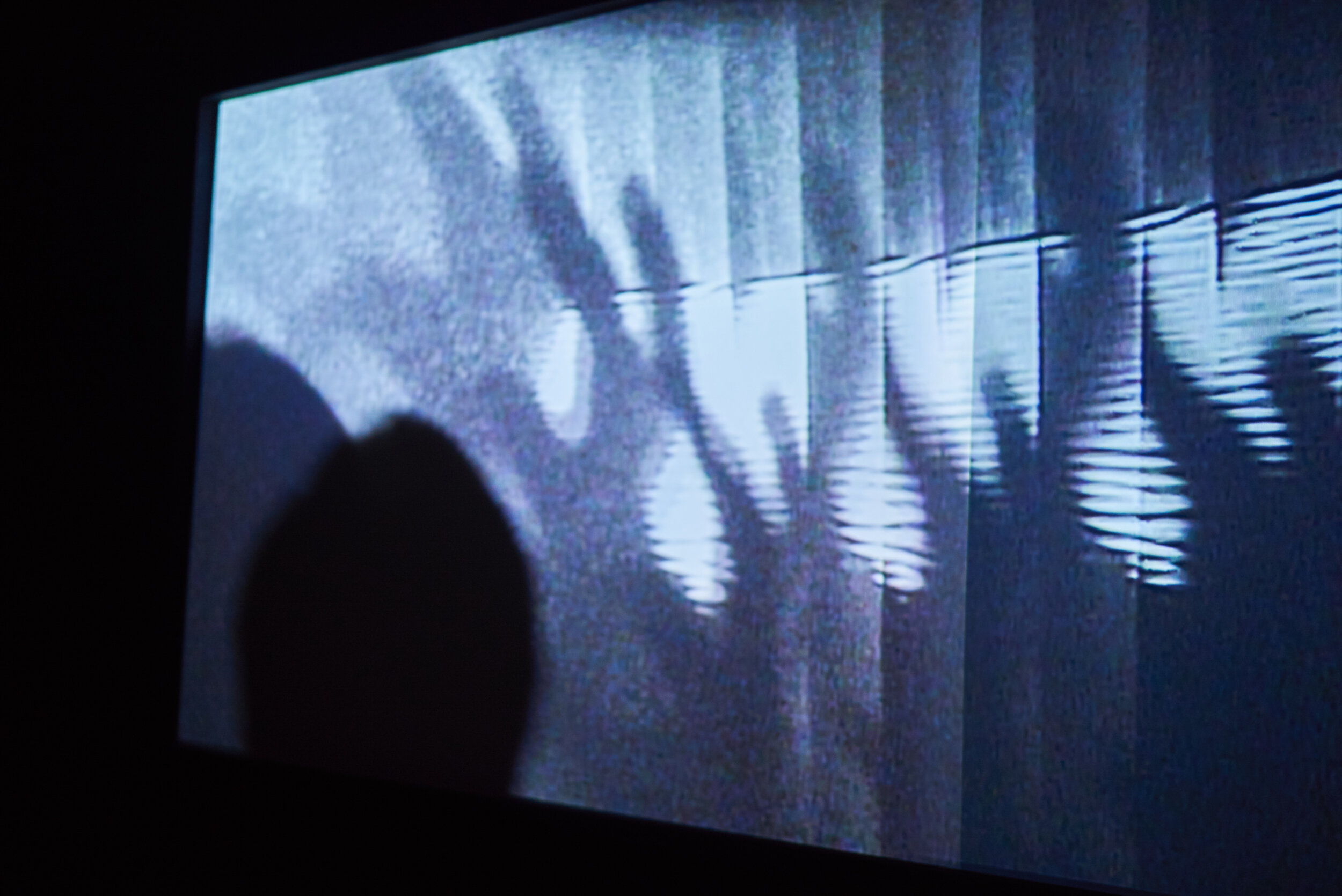

Walking blindly next we encounter a carnal scene captured on a distorted video that brings forth technology’s intimate relationship with the erotic. As Baudrillard reminds us, “pleasure (whether perverse or not) is always mediated by a technical apparatus”. The Cave (2019) brings us into the simultaneous dystopian worlds of Ballard, Huxley, and Richardson. Here a rapid transformation takes place - from the dematerialization of the self in Going Grey to the urgent physical desires of two lovers in a darkened room in The Cave. We, the viewer/voyeur, have the privileged vantage point of observing the couple through angled slats - their bodies reproducing. Our desire to access them is at once repulsive and overwhelming. We can see their bodies (which appear life-sized) - which begs the question, can they see us?

This public display of arousal is the apex of a culture consumed by online exhibitionism and symbolizes the pornographic impulse to broadcast ourselves with utter granularity. In Huxley’s Brave New World sexual pleasure is a regulated commodity administered formally by the state in order to ensure that citizens are too preoccupied to be troubled by their own disenfranchisement.

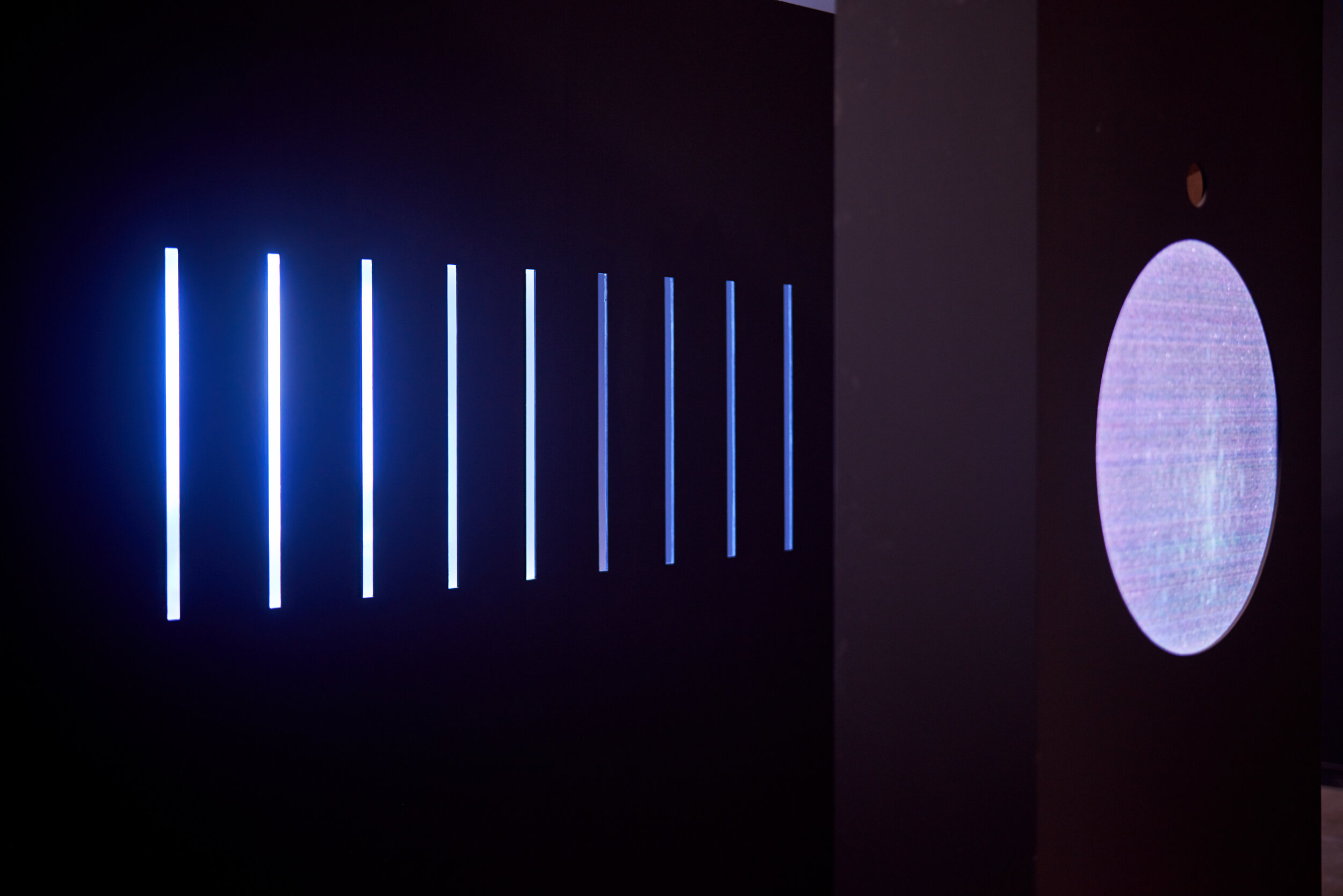

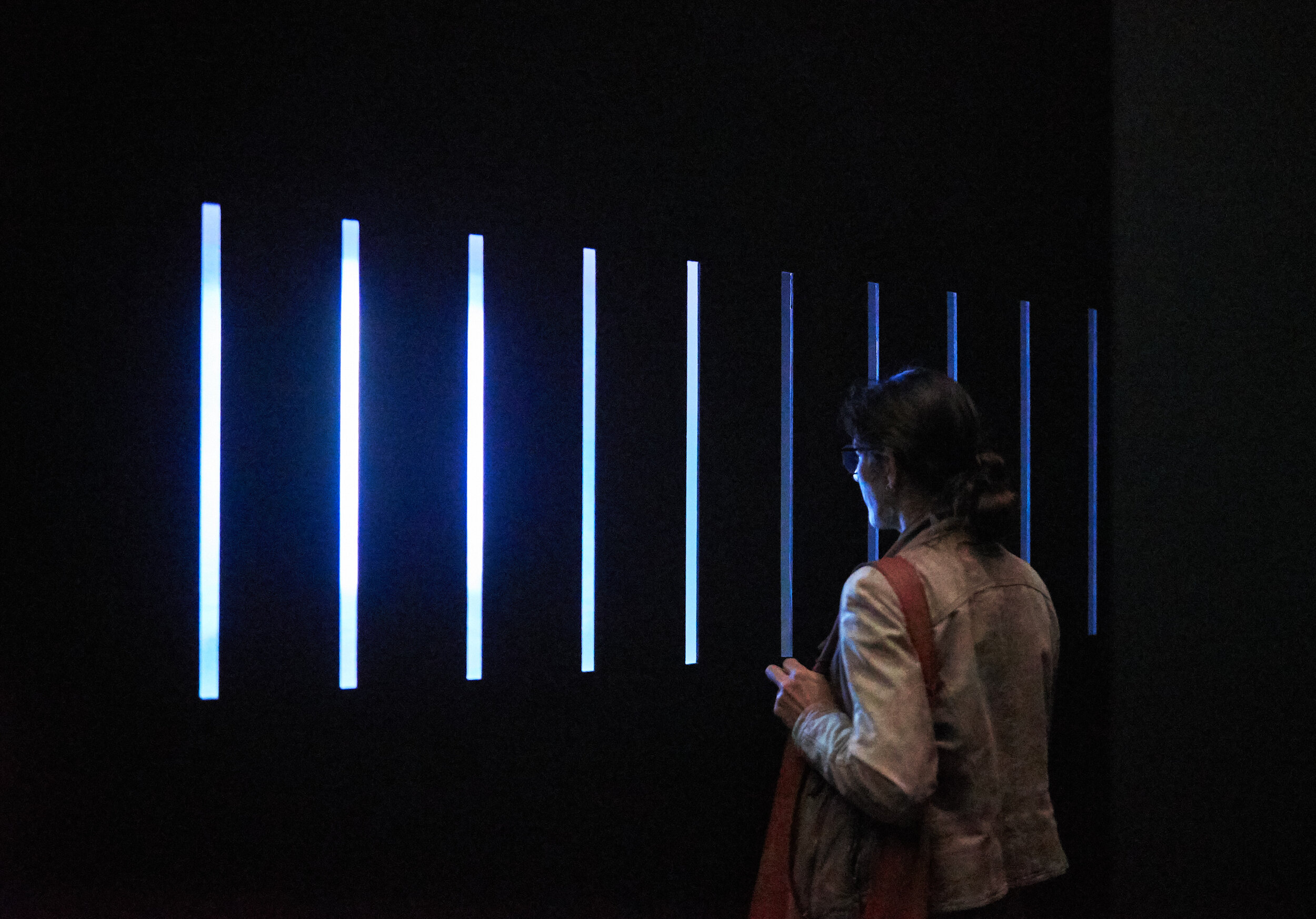

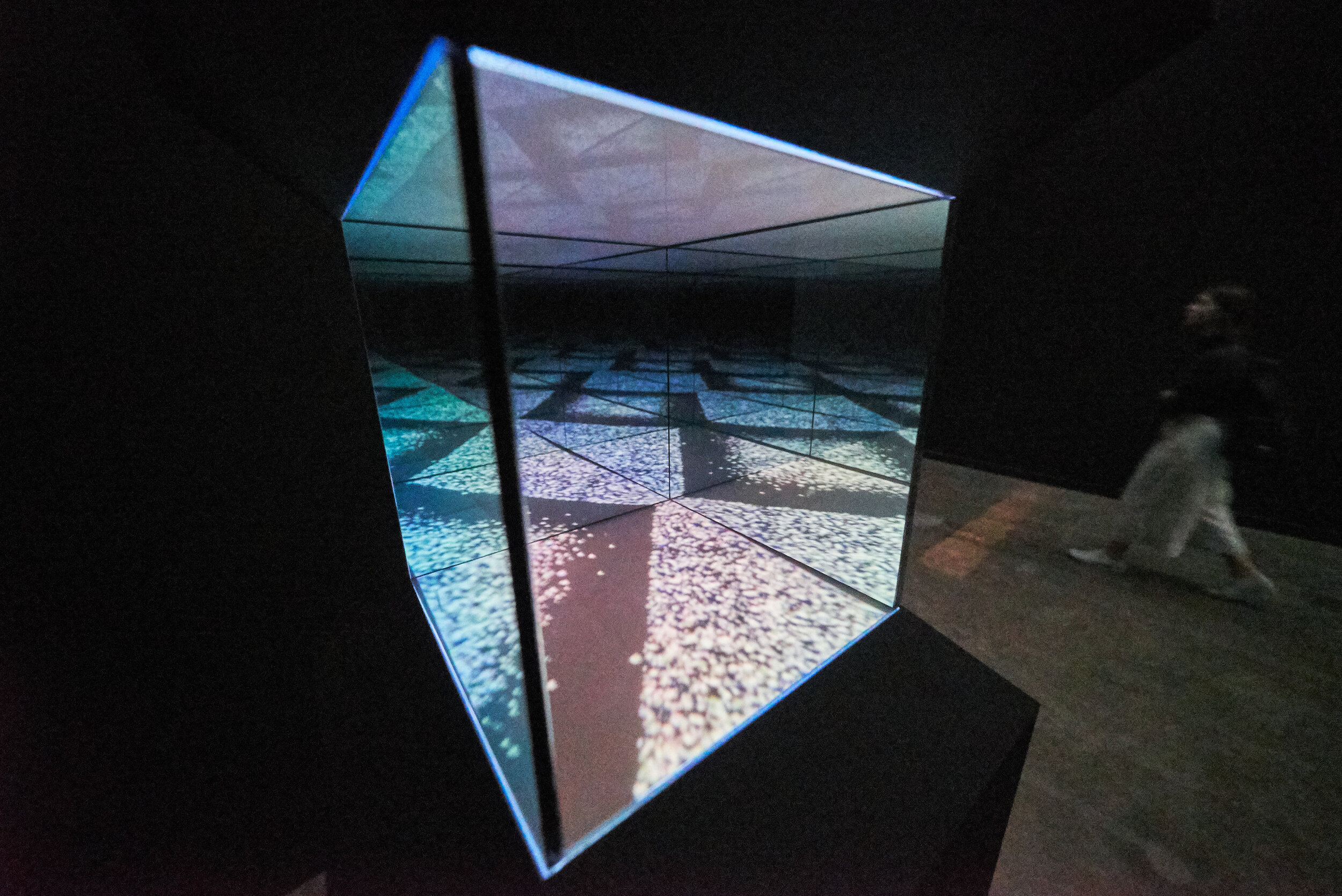

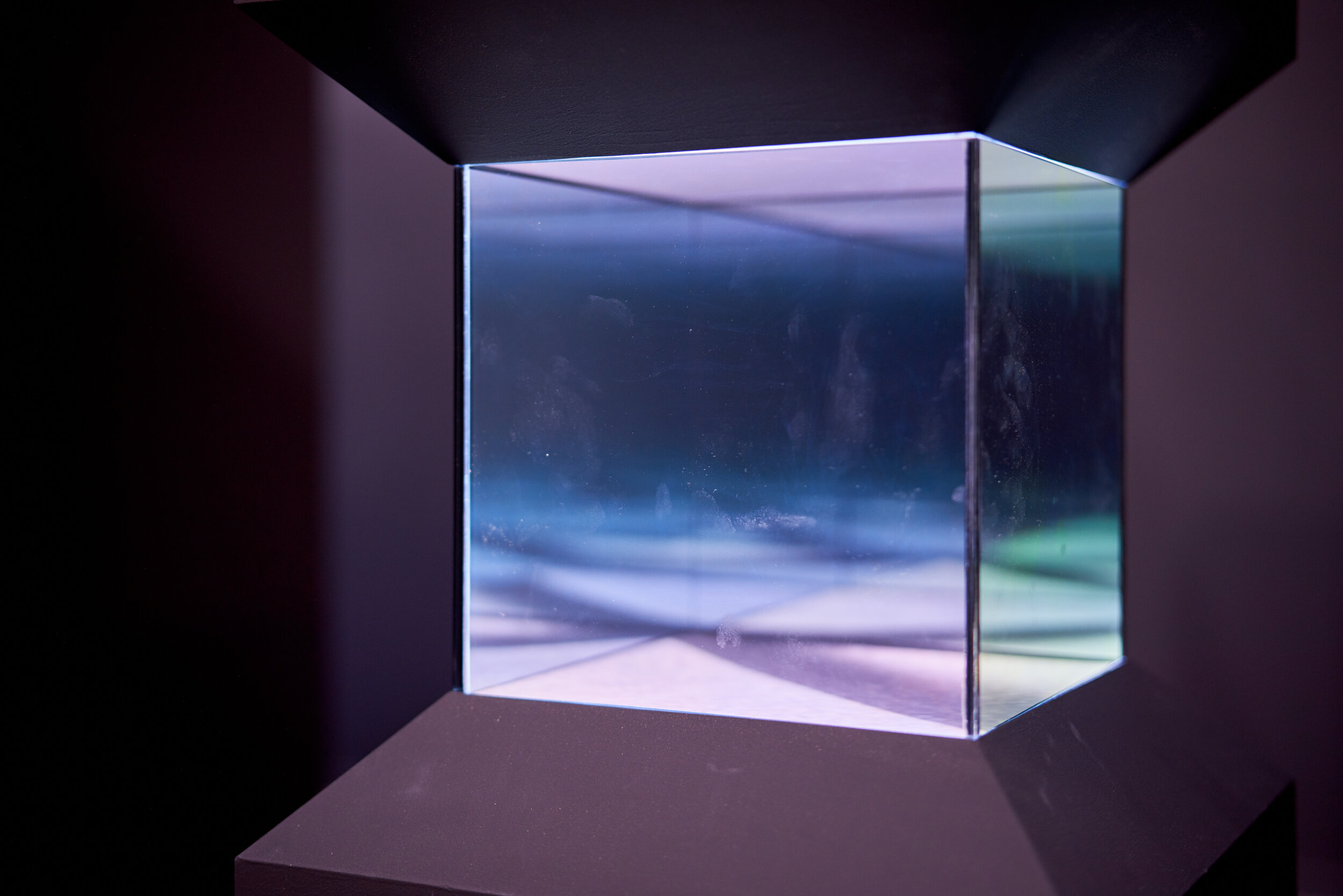

Continue on through the hall to find Sands Stand Still (2019) – a time piece, made of electricity and glass. It is enormous and suspended - a monolithic doomsday clock - a watch in all its meanings.

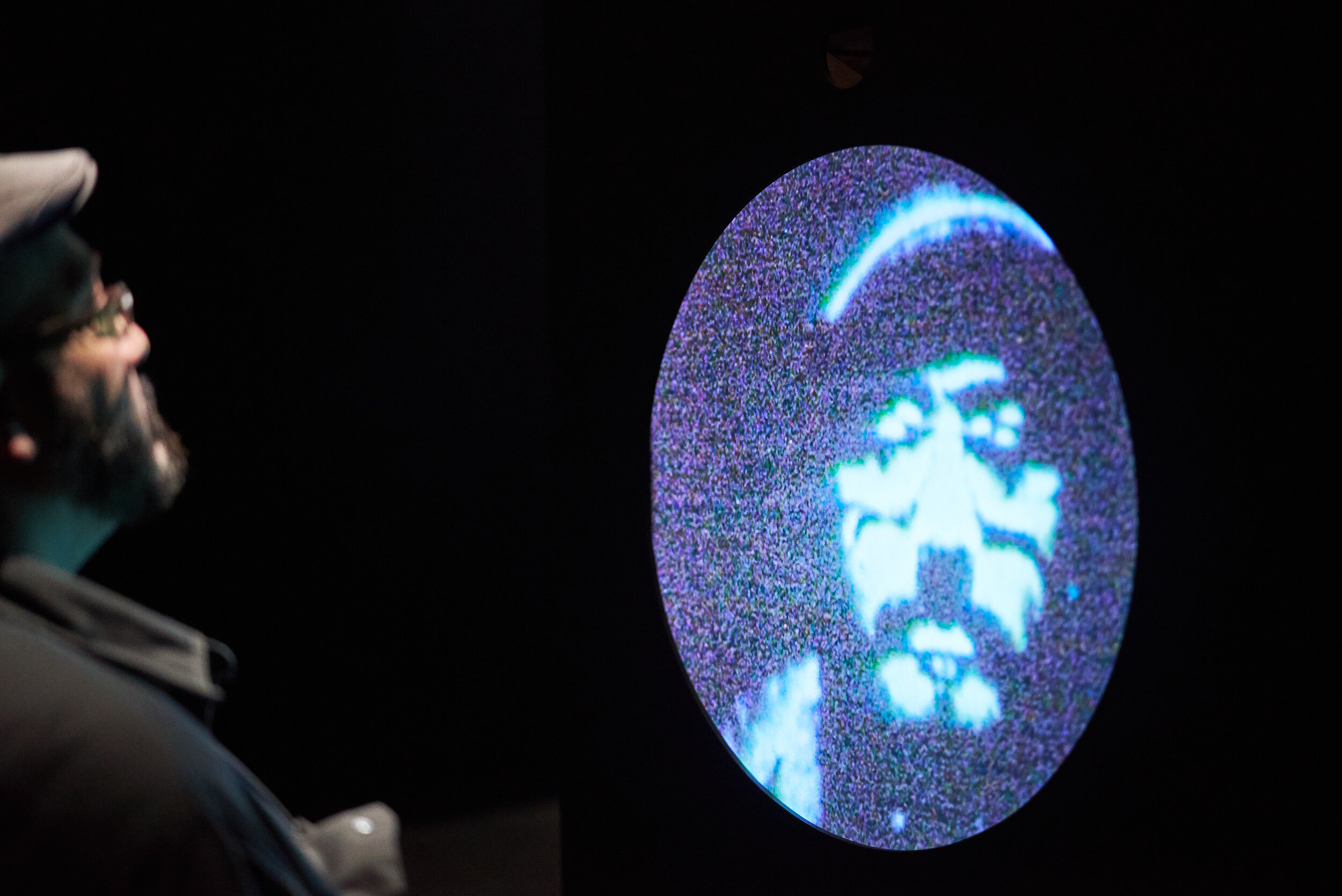

Sphere of Influence, Circle of Protection (2019) continues the visceral onslaught. In a climate where affect has been numbed, like Ballard’s wayward characters, we seek out tableaus of incredible violence, simply to experience something beyond our tepid baseline. Sphere of Influence presents a complex arrangement of elements that succeeds in this elicitation - but the feelings it conjures are not necessarily the ones we seek (is a distressing feeling better than no feeling at all?). As Baudrillard remarks in Simulations, the 21st century body is one “confused with technology in its violent and violating dimensions”.

The relentless streams of automobile accidents that compose the piece have been captured by dash cams--used electively by some, and mandated by nations like Russia for others. This constant supervision - whether state-led or self-imposed - firmly describes again our contemporary media landscape. The artwork’s layout, in the form of a vanity mirror, recalls the self-surveillance of social media and our willingness to report constantly on our own location, consumer habits, and demographic information often in exchange for a free wifi signal - that connects us to a system that feeds off of an insatiable need it has manufactured.

In this room, the midway point in the maze, car crashes assault our eyes. Right before the moment of impact, a flashbulb further obscures our vision. Here blindness is the only way to escape this nightmare.

Meanwhile, Fire and Theft (2009) is an immersive panorama of international cityscapes. Each vantage point captures the sun at varying moments in its cycle. This work permits the impossible experience of being everywhere at once - a phenomenon enabled by our advanced digital devices. This omniscient power, of course, has consequences that recall Icarus who paid the ultimate price for flying too close to the sun. Yet the title of this work seems to refer to another Greek myth, that of Prometheus, who defied the gods by stealing their fire and giving it to humanity, thereby enabling the formation of civilization. For this act of betrayal Prometheus was doomed to his own cyclical torment - chained to a mountain to have his liver pecked out by an eagle, only for the organ to regenerate and to be pecked out again the next day.

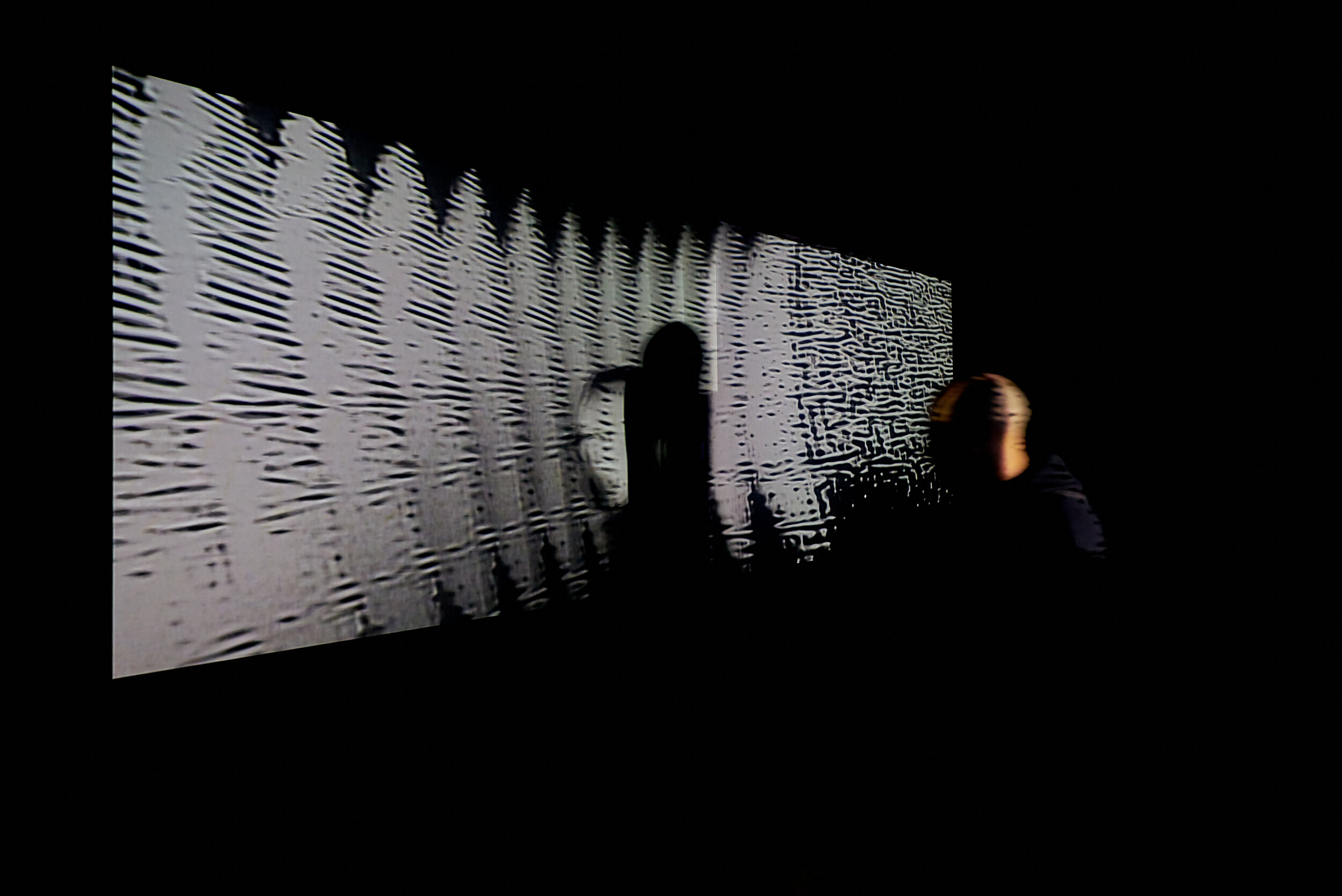

The final work in the exhibition, Ouroboros (2019) provides some salvation in an otherwise hopeless communications circuit. Two cameras observe each other’s projected outputs. Tiny shadows are generated by the imperfections of the gallery wall. The iterations magnify and mutate into fragmented organic patterns. The two video images are also pushed into an audio channel abstracting the image even more so. Tones of black from the video feed are interpreted as shades of silence and white is translated to full noise. The image and sound continually evolve and are affected by the shadows we cast.

The cyclical and unsettled motif of the feedback loop holds a multitude of meanings within Kali Yuga. It is at once the aesthetic of a decayed civilization and the symbol of the relentless pattern of birth, death, and rebirth central to Hinduism. According to its scriptures, at the end of this age of vice the world will suffer a fiery cataclysm that will in its wake destroy all evil and the universe in its entirety, only for it all to be created the next day, anew.

Notes:

1. Ballard, J.G. “Some Words About Crash.” Foundation: The Review of Science Fiction, Edited by Peter Nicholls, No. 9, 1 Nov. 1975.

2. Goldberg, David. “The Interface of Technology and Eroticism in J.G. Ballard’s Crash” 1996, www.cyberartsweb.org/ cpace/body/dgmt/main.html.

3. Ballard, J.G. “Some Words About Crash.” Foundation: The Review of Science

Fiction, Edited by Peter Nicholls, No. 9, 1 Nov. 1975.

4. This concept was later bolstered by Frederic Jameson’s famous description of the “waning of affect” which appeared in Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, 1991. p.11.

5. Ballard, J.G. “Some Words About Crash.” Foundation: The Review of Science Fiction, Edited by Peter Nicholls, No. 9, 1 Nov. 1975.

6. Ballard, J.G. “Introduction.” The Atrocity Exhibition, by V. Vale and A. Juno, Cape, 1970.

7. Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

8. Ibid.