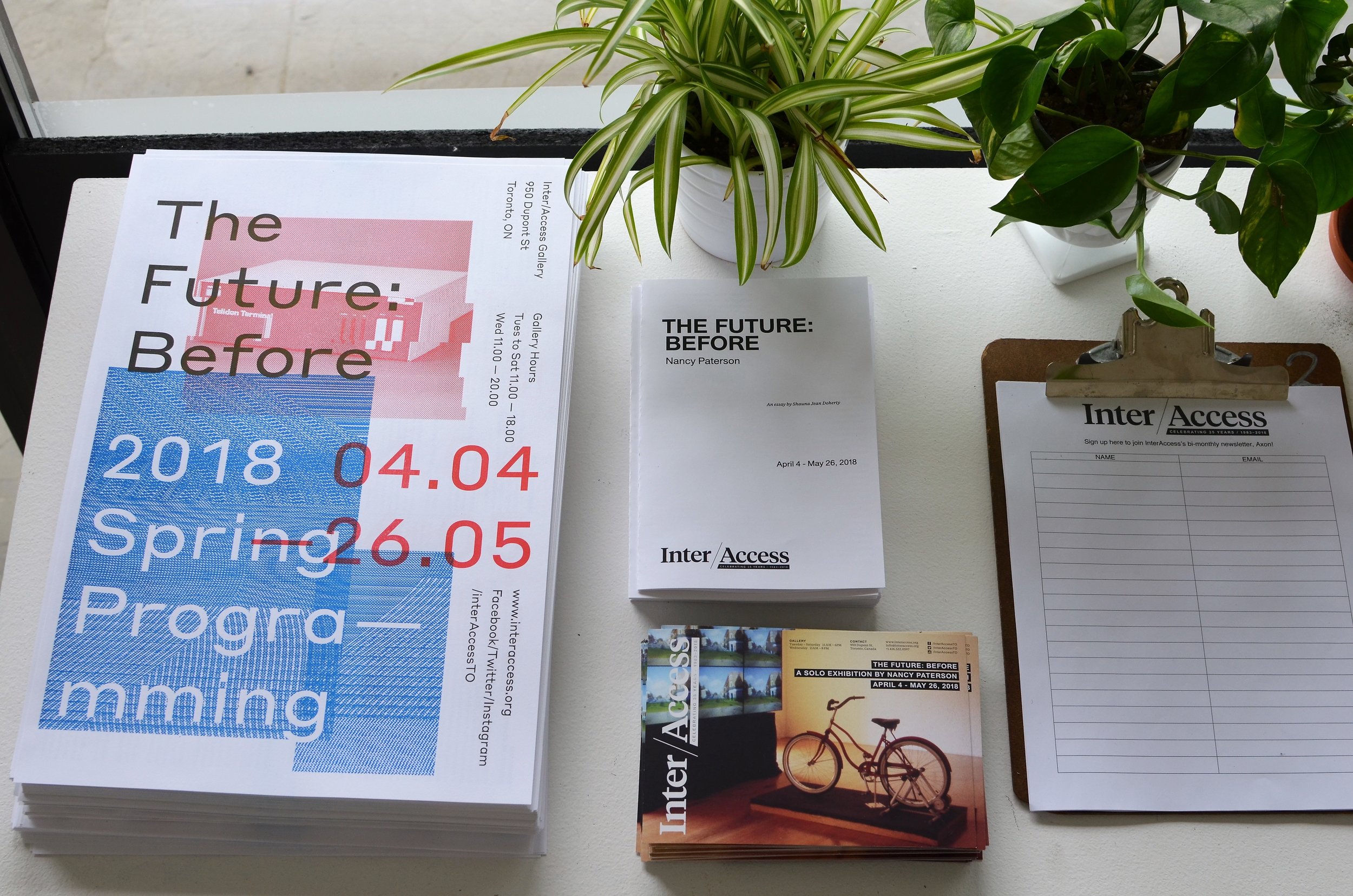

The Future Before

A solo exhibition by Nancy Paterson

April 4th - May 26th, 2018

InterAccess

950 Dupont St.

Role: Curator

The Future: Before is a retrospective exhibition of works by pioneering Canadian media artist Nancy Paterson. Paterson’s career has spanned 30 years and her influence has been felt both nationally and internationally in the field of new media art. Through the unique application of custom-made equipment, Paterson’s works are socially critical and technically complex, expressing a feminist perspective on the impacts of technology in society.

This exhibition animates interactive works by the artist that have never been exhibited in Toronto. Two of Paterson’s most widely known works will be on view: Bicycle TV (1989) and The Machine In The Garden (1993).

Paterson’s activities as an artist, writer, curator, and educator have developed in many ways in parallel with InterAccess and Toronto’s electronic art scene. Over several decades Paterson has been an active member of InterAccess in a variety of capacities: as a guest curator (with the online and offline group exhibition Disembodied in 1997), featured artist (in the exhibition Game Girls in 1999 and Meantime to Upgrade in 2014), panel discussant (in the NERVEgate Conference in 1997 and the Subtle Technologies Conference in 1999) and as a workshop participant.

Addition Programming:

The Basement Tapes, Media Arts Colloquium

Where Are We Now? Feeling Our Way in Post-Cyberfeminist Space, Lecture

Nancy Paterson, Artist Talk

Exhibition Essay

The first cyberfeminists of the late 20th century conceptualized a utopian alternative to patriarchal society set to unfold in cyberspace where gender constructions and sexual difference could dissolve into the cybersea. The exhibition The Future: Before features media artist Nancy Paterson, an early reflector on the topic of cyberfeminism. Her body of work, developed over the last 30 years, shares with it qualities that characterized the cyberfeminist movement that she helped to establish. Early cyberfeminist critiques of technology observed the assumed masculinity underlying digital technologies, with a particular concern surrounding the macho culture that pervaded the early Internet, in addition to its military origins.1 Premillennial cyberfeminists, including Paterson, sought to counteract the reproduction of patriarchal notions of the gaze, domination, and power underlying digital technologies, through the subversive use of those very tools.

Though she never imagined a world (whether real or virtual) unbound by gendered experience, scrutinizing the relationship between gender and technology is the bedrock of Paterson’s practice. She consistently wields technology with liberatory aims while maintaining a pointed suspicion of the utopian idealism that was heralded by the cyberfeminists of the 1990’s. This wariness extends to other forms of utopian promise invoked by technological progress, including the 1950’s idealism of the labour-reducing capacities of new domestic technologies and a generalized critique of the legacies of 19th century technological determinism. Concentrating on the naive sensibility that technological progress is inevitable, neutral, and good, Paterson deploys her version of cyberfeminism in order to challenge this essential ideology.

As Paterson wrote in one of the earliest texts clarifying the field, “Cyberfeminism does not accept as inevitable current applications of new technologies which impose and maintain specific cultural, political, and sexual stereotypes. Empowerment of women in the field of new electronic media can only result from the demystification of technology, and the appropriation of access to these tools”.2 Empowerment through technology has been a persistent theme throughout Paterson’s career, both materially and conceptually. One of the strongest voices in the Canadian new media art scene throughout the 1990’s, Paterson has dedicated her technical savvy and mechanical knowledge to critiquing the cultural and social impacts those technologies advance.

Two of Paterson’s earliest video sculptures are on view, Bicycle TV (1989) and The Machine In The Garden (1993). Both immersive and interactive, the artist creates environments that invite the viewer to confront the power dynamics embedded in technoculture and question their place within digital space. The pieces featured in this exhibition assemble the main concerns present in Paterson’s practice, the intersections of power, technology, and culture and invite the viewer to engage in two different ways: Bicycle TV incorporates the viewer physically while The Machine In The Garden implicates through involvement. Here, Paterson contrasts the promise and optimism of technological progress with the lived and ongoing realities of inequity and social and political upheaval.

The artist’s attention to interfaces extends her reflection on the underlying mechanisms that govern technological devices, deepening her investigation of how they function in our lives. In both Bicycle TV and The Machine In The Garden the viewer accesses the artwork through a unique portal, the bicycle and the slot machine, respectively, that demand the engagement of the physical body. Paterson’s interfaces are remarkable but unobtrusive, allowing the viewer to navigate her simulated realities unencumbered, producing a sense of exploration and discovery. While seamlessly transporting the viewer to a virtual environment, Paterson’s works critique the real world.3

Bicycle TV invites gallery visitors to immerse themselves in an interactive and tranquil tour of small town Ontario, in real-time. Gallery goers are encouraged to mount the 1950’s era bicycle. Pedaling activates the work, transporting the viewer to the streets of Bracebridge. The user assumes a simulated sense of control – managing the speed, direction, and duration of the experience, assisted by sensors at the front and rear of the mechanism. This sensation of dominion dissolves as soon as the viewer finds themselves returning to the intersection where they started their route, discovering the confines of the world Paterson has created.

Demonstrating a sophisticated use of laserdisc technology, Bicycle TV distinguishes itself from other interactive virtual worlds that came before and after it, opting for the representation of a natural environment rather than a simulated space developed through computer graphics, to immerse its viewer in the hyper-real. The rider’s experience is charmingly optimized through Paterson’s use of picture in picture inlays that highlight additional sights along the journey.

Bicycle TV inserts the viewer into a picturesque landscape, removed from a global context and permeated by nostalgia. The quaint backdrop however, bellies the events that were unfolding in 1989 in corners of the world far from Bracebridge, Ontario: protests in Tiananmen Square, the Montreal Massacre, and the fall of the Berlin Wall. As the global landscape drastically shifted, 1989 also welcomed the first commercially available Internet service providers as well as the first orbiting GPS satellite. As gallery visitors tour the timeless streets and paths of the southern township, Bicycle TV appears as a VR prototype, presaging the way in which VR technology would be used in the future to escape from present day realities.

The sublime environment Bicycle TV suggests can be made possible through technology is immediately challenged by the show’s second interactive piece, The Machine In The Garden. By placing these works side by side this exhibition physicalizes the boundary between nature and culture and technology’s capacity to efface reality or confront one with it. The two works are in dialogue, contrasting the idealism of the natural world with the realities of social discontent and conflict brought upon or exacerbated by technological “progress”.

The Machine In The Garden examines the effects of mass media – flattening the depth of human experience by bombarding the viewer with a deluge of television imagery. Viewers are invited to pull the lever or push the button on the front of the slot machine, activating the work’s three digital screens. A random selection of video material is triggered, erupting in a cacophonic assemblage of sound and images - of war, talking heads (game show hosts and religious figures), and children’s television programming. The segments gradually increase in speed, while wipe edits transition between the video clips. The sequences end on each screen at staggered moments mimicking a slot machine’s well known routine, finishing with the appearance of a woman, repeated on each monitor, gesturing the Buddhist edicts, SEE NO EVIL, SPEAK NO EVIL, HEAR NO EVIL. There are 29 possible combinations that can result from pulling the slot machine’s arm, all enabled by Paterson’s custom-designed A/V controller and three laserdiscs resurrected from the artist’s personal collection.

Here, Paterson represents contemporary culture (circa 1993) through the display of media images and mainstream commercial narratives and suggests the existence of an underlying order within the appearance of chance or chaos. By presenting the viewer with this material, Paterson creates an awareness that has the potential to dismantle the dominance of these representations. Additionally, as curator Liane Davison writes, the work suggests that “Playing the odds and betting to win is a decidedly postmodern response to a failing faith in technological utopianism”.4

As David Rokeby noted in his 1996 essay “Transforming Mirrors”, interactive artworks create the conditions for viewers to reflect on their own agency and status within a larger social system. Paterson’s The Machine In The Garden directly achieves this potentiality, “By providing us with mirrors…interactive artworks offer us the tools for constructing identities, our sense of ourselves in relation to the artwork, and by implication, in relation to the real world”.5

Engaging this work from a contemporary perspective infuses it with additional meaning. The habit forming potential of gambling is here mapped onto the addictive nature of our digital devices. The endless onslaught of media images that comprise this work are not unlike the endless Facebook threads or Tumblr feeds that have come to punctuate our everyday experience. The seemingly infinite flow of information made accessible by technology has only intensified in the last three decades since this piece’s creation.

Finally, a portion of Paterson’s mousepad collection is installed in the gallery. An irreverent assemblage of now antiquated technomaterial illuminates the speed at which technology changes. The quirky computer accessories are elevated to the status of fine art object, a gesture that perfectly materializes the wink that subtly accompanies much of Paterson’s art and life.

From a vantage point, almost 30 years on, it’s abundantly clear that the post-patriarchal society envisioned by cyberfeminists of the 1990’s has not come to pass. Optimism surrounding the Internet’s emancipatory capacity and ability to dismantle hierarchies of power has largely dissipated. As noted feminist artist and prominent critic of the early cyberfeminist movement, Faith Wilding, aptly observed in a text titled “Where is the Feminism in Cyberfeminism”, “[the Internet] is already socially inscribed with regard to bodies, sex, age, economics, social class, and race”.6

The Future: Before unfolds in a moment that has been deemed post-cyberfeminist7 , where women all over the world continue to connect online in order to disrupt “racial and gender privilege”8 and interrupt the “patriarchal trajectory of technoculture”.9 As contemporary feminist media artists continue to find new ways to interrogate the impacts of digital technologies along gender lines, technoculture continues to mediate and exacerbate gendered experience. It seems Paterson’s advice from 1990’s remains prescient, it is the responsibility of technology’s users to intervene, steering the ship in order to avoid getting caught adrift in the seemingly boundless cybersea.

Essay Notes

1. Tenhaaf, Nell. “On Monitors and Men and Other Unsolved Feminine Mysteries,” Critical Issues in Electronic Media, State University of New York Press, 1995, pp. 219–234.

2. Paterson, Nancy. “Cyberfeminism,” Nancy Paterson: Mediaworks, Surrey Art Gallery, 2001, pp. 59–63.

3. Paterson’s works suggest a further awareness that interfaces are often constructed from a gendered (namely male) perspective and possess the capacity to non-neutrally reproduce conventions of corporeality, domination, and control.

4. Nancy Paterson: Mediaworks, Surrey Art Gallery, 2001, p. 48.

5. Rokeby, David. “Transforming Mirrors,” 1996, .

6. Wilding, Faith. "Where is feminism in cyberfeminism?," n.paradoxa international feminist art journal, special issue: Women and New Media, KT Press, July 1998, pp. 6–13.

7. Hester, Helen. “After the Future: n Hypotheses of Post-Cyber Feminism,” Res., 2017.

8. Scott, Izabella. “How the Cyberfeminists Worked to Liberate Women through the Internet,” Artsy, October 2016.

9. Cutler, Randy Lee. “Remapping the terrain,” Nancy Paterson: Mediaworks, Surrey Art Gallery, 2001, pp. 23–29.